There has been a surge in demand for hepatitis C tests since the BBC revealed that hundreds of people in the UK were unknowingly infected with the virus, the Hepatitis C Trust says.

Up to 27,000 people caught it when they were given transfusions with infected blood from the 1970s until 1991.

According to BBC analysis, a further 1,700 people who caught it in the same way have not yet been diagnosed.

Left untreated, hepatitis can cause chronic liver disease and can be fatal.

Known as the “silent killer”, hepatitis C may cause few symptoms initially, with early signs including night sweats, brain fog, itchy skin and fatigue. But for every year a person carries the virus, their chance of dying from liver cirrhosis and related cancers increases.

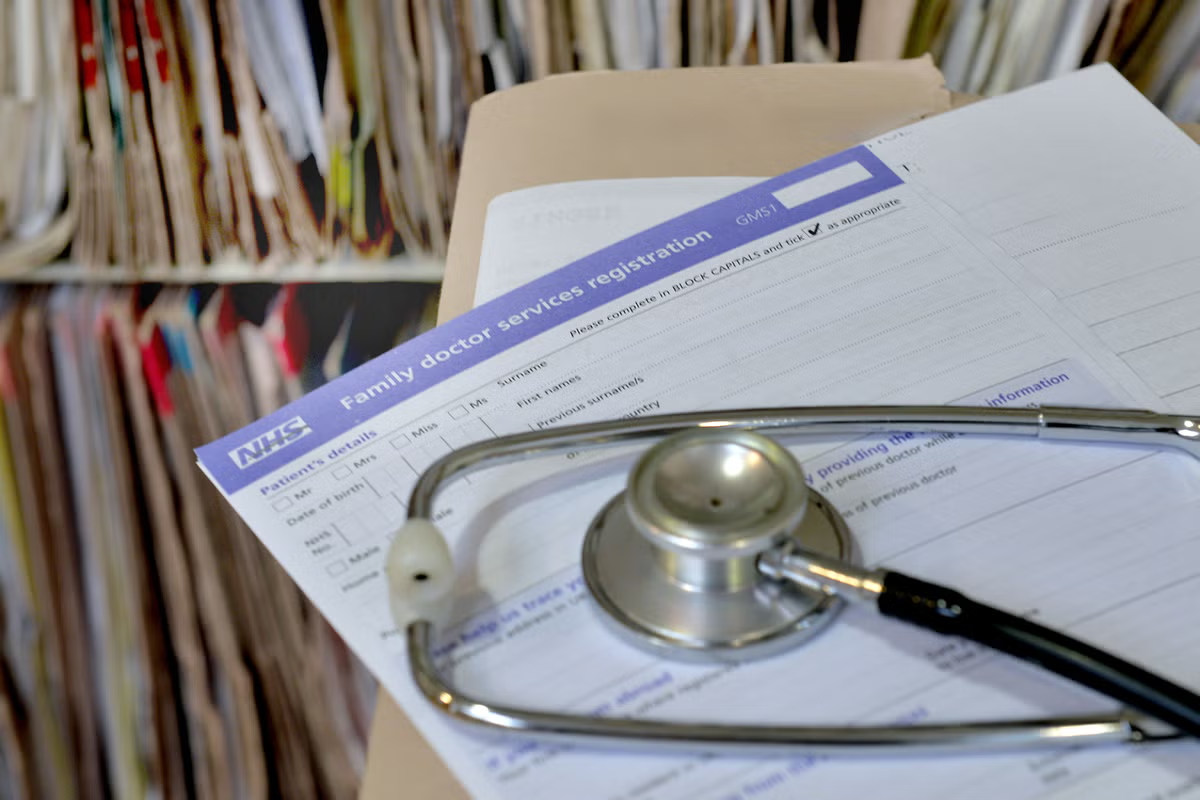

The Hepatitis C Trust told the BBC 12,800 people in England have requested NHS home-testing kits in just over a week, compared with 2,300 in the entire month of April.

The charity said it had been “inundated with callers across the UK seeking further advice and testing”.

“It has been incredible seeing the response from the public as they have become more aware of the risks of hepatitis C,” said Rachel Halford, from the charity.

“Most people who get tested will receive a negative result and have peace of mind, but it is important to find those individuals who are unaware of their status so that we can get them access to a simple and effective treatment.”

The Sunday Times has reported, external Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will soon unveil a compensation package for those affected by the infected blood scandal.

In an interview with the paper, Mr Hunt said he intended to fulfil a promise he made to a constituent who died after being affected by contaminated blood.

An official announcement from the government is expected following the publication of the final report from the infected blood inquiry on Monday.

The BBC recently exclusively revealed the true scale of undiagnosed cases of the disease, related to the infected blood scandal.

The BBC’s calculation of 1,700 undiagnosed cases is based on statistics submitted to a public inquiry, external into the infected blood scandal, as well as Freedom of Information requests to infected blood support schemes.

Official documents, seen by BBC News, revealed how the UK government and the NHS failed to adequately trace those who were most at risk of having the virus.

The BBC also revealed how the authorities actively tried to limit the public’s awareness of the virus to avoid embarrassing “bottlenecks” at hospital liver units. Testing was limited because of “resource implications for the NHS”.

Charlotte Dickens, 70, is among those to have asked for a home-testing kit following the publication of this story, and is awaiting the result.

Ms Dickens, from Surrey, had a blood transfusion after suffering a haemorrhage during childbirth in 1980. She said she was “astounded” that she and others were not tested for the disease once the risks became clear.

When news of the scandal first broke, she assumed she was not affected. “I had no idea it [hepatitis C]could linger around and cause liver cancer. Why didn’t we all get tested, what’s the answer to that? It is hard to find an excuse.”

Ms Dickens added that she felt she should speak up due to the many people who have died as a result of the scandal.

About 3,000 people are known to have died as a result of receiving infected blood products.

But it is believed that many people who unknowingly contracted hepatitis C have also died.

Victoria Arkley recently told the BBC she was angry that her mother Maureen died from liver cancer soon after being diagnosed with hepatitis C.

She believes she was infected during transfusions 47 years earlier: “Where was the public health campaign? Why didn’t the doctor test her? They knew she had had transfusions, but no one tested her. I’m so angry.”

The infected blood scandal is considered to be the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history.

More than 30,000 people in the UK were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood products, from the 1970s to the early 1990s.

Most of those affected were people with blood disorders such as haemophilia, or people who had received blood transfusions.

Due to a shortage of blood products in the UK, many were obtained from the US and had been bought from high-risk donors such as prisoners and people who misused drugs.

Even though hepatitis C was not formally identified until 1989, health officials and NHS staff recognised that this form of hepatitis could be fatal as early as 1980.