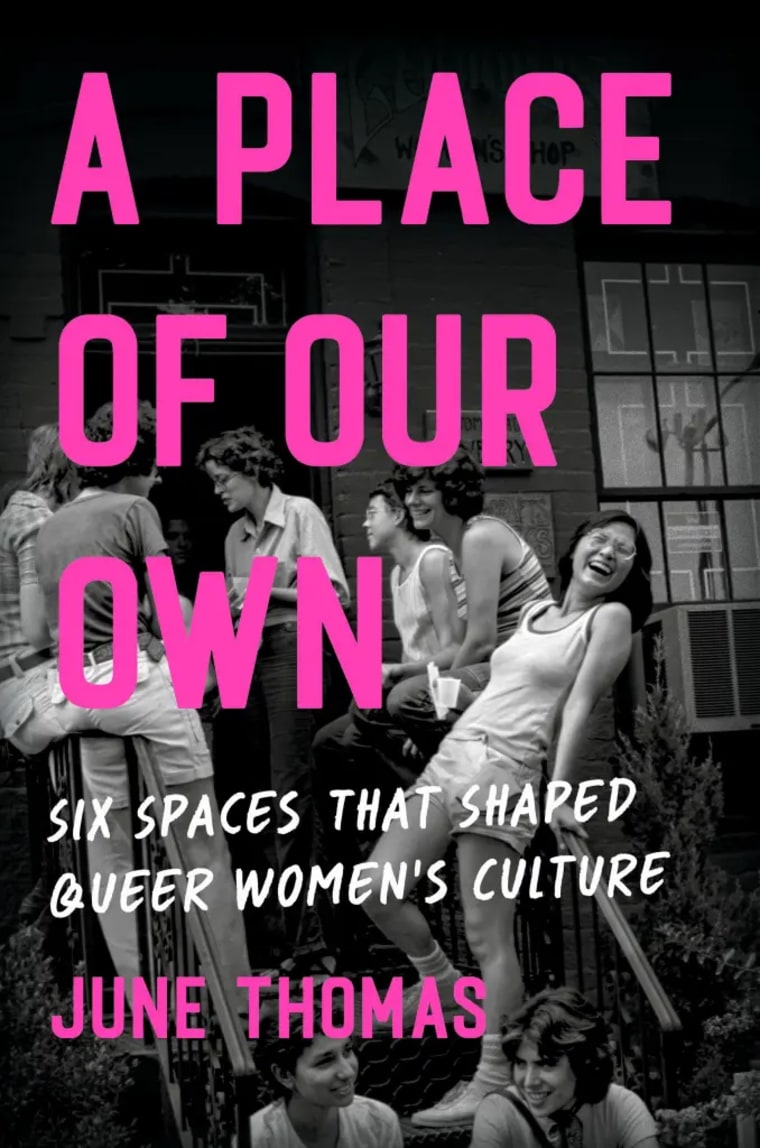

Author and journalist June Thomas hadn’t been to a softball game until 2022, when she was researching for her new book, “A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture.” She admits that’s odd for a queer woman, especially one who considers herself an expert on the spaces her community occupies.

“I’m very much an indoor person,” Thomas joked about her absence on the field.

The softball diamond is one of six essential queer women’s spaces Thomas writes about in “A Place of Our Own,” her new cultural history that comes out Tuesday. She also explores lesbian bars, feminist bookstores, rural lesbian separatist communities, feminist sex-toy stores and LGBTQ vacation destinations like Cherry Groveand Provincetown. It’s a list, Thomas told NBC News, that she curated with a desire to document spaces that queer women could “shape and change.”

“They all shaped what we now think of as lesbian culture, and they all have lessons to teach readers — queer and straight alike — about the history of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,” Thomas writes in the book’s introduction. She adds that bisexual, transgender and other queer women have also played central roles in these spaces.

Another priority for Thomas was to describe the personal risk it took for generations of queer people to take part in these physical locations. During the Lavender Scare, a period from the late 1940s through the ’60s in which thousands of gay men and women in the federal government lost their jobs over fears of communist ties, many women opted to go to private parties over lesbian bars for fear that they would be caught up in a police raid. Other women were careful to travel to neighborhoods far from their own lest they be seen by friends or family, Thomas writes.

“I wanted to at least try to help people get a sense of just how challenging it was, how much justifiable fear and danger there was in going to these spaces,” she said.

While lesbian bars are arguably the most well-known queer women’s spaces Thomas writes about, their numbers have diminished at a particularly stark pace over the past few decades. Despite experiencing a renaissance in the last few years, the number of lesbian bars in the U.S. has shrunk from about 200 in the 1980s to about 35 in 2023, according to an NBC News tally. Thomas finds this decline “bananas” and celebrates the needs these businesses fulfilled for generations of queer women, herself included.

A half-century ago, “the only place that you could have any hope of expressing your feelings of being open, of just not having to hide and lie,” she said, “was in a lesbian bar.”

Now, she’s grateful that many lesbian bars have evolved to include a wider clientele. The Cubbyhole in New York City (made famous when Madonna made a nod to the bar during a 1988 interview on “Late Night With David Letterman,” according to the book) now says on its website that it’s “a safe space for all,” while its nearby neighbor Henrietta Hudson states it’s “a queer human space built by Lesbians.”

“It’s hard enough to go into a space to meet people. That’s enough stress already,” Thomas said. “Being able to let down your guard, that is still important. But I think there are more places where that is possible now than there have ever been before.”

The evolution of queer women’s spaces was often spearheaded by women of color, who for decades were not as welcome into many of the most popular lesbian bars. Thomas writes about the Shescape 7, a group of Black and Latina women, including the award-winning writer Jacqueline Woodson, who in 1986 filed a complaint with the New York City Commission on Human Rights alleging discrimination by the organizers of a popular women’s party in the city.

“Anyone who entered a lesbian club in this period could see who was allowed in and who was kept out,” Thomas writes.

Thomas emphasizes that many women were “very specifically trying to have a place that was quieter, a place that didn’t have booze.” Feminist bookstores, which she describes as “spaces of lesbian enlightenment” that hosted everything from author readings to 12-step programs, were one such space.

These bookstores were particularly important for Thomas, who said “you go to a bookstore to find out who you are.” In her book, she recounts working at the feminist bookstore Lammas in Washington, D.C., in the 1980s, and finding an apartment when she moved to Madrid, thanks to a bulletin board at Librería Mujeres.

But the rise of online shopping and large retail chains in the 1990s made surviving as an independent bookstore especially difficult, Thomas writes. She goes on to detail the plight of Amazon Bookstore Cooperative, a Minneapolis destination for feminist literature founded in the 1970s that shuttered after a yearslong legal fight with Amazon.com over their competing names.

“It’s all too easy to see the mass closure of feminist bookstores as a failure,” Thomas writes. “But the women who created and toiled in those stores weren’t motivated by thoughts of longevity. Their goal was to establish locations that would transform the lives of the women who walked through their doors. By that measure, they were hugely successful.”