Race Across the World contestant Betty Mukherjee has been praised after she shared her diagnosis of Mayer Rokitansky Küster Hauser syndrome (MRKH) on this week’s programme.

Speaking to BBC News, Betty said she was nervous for the episode to go out, but the widely positive response has been “overwhelming in the best way”.

MRKH affects 1 in every 5,000 women, according to the NHS.

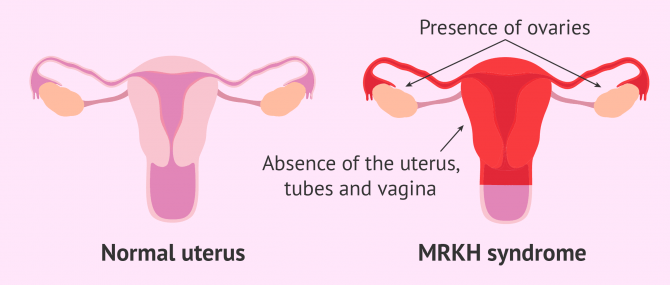

It mainly affects the reproductive system, where women are either born without a vagina and uterus, or the vagina and uterus fails to develop fully.

MRKH is a congenital abnormality, meaning it is something people are born with – although many are not diagnosed with it until their teenage years.

This was the case for Betty, 26, who was paired with her brother James for the BBC One series, on which she revealed she was diagnosed shortly after she turned 16.

“As a young woman, you’re kind of told ‘you’re going to marry, you’re going to have a family’,” she said on Wednesday’s episode.

“From a young age, when that’s taken away from you, it does put doubts in your mind and doubts in your purpose as a person.”

Betty doesn’t have a womb and only has one kidney as a result of the condition.

At first, Betty was in two minds on whether to talk about her diagnosis on the programme, she told BBC News.

“When I got diagnosed, I had never heard of it before – and now it’s quite clear that so many people haven’t heard of it,” she said.

She said raising awareness was one of the reasons she decided to talk openly about it.

“If it can help someone, and for someone who might just be getting their diagnosis to say ‘that’s ok, I’ve heard of it before, this person has talked about it’,” she added.

Betty said there was a lot of anticipation in the lead-up to the episode being aired, and not knowing how people would react was the “scary part”.

“But it couldn’t have gone any better,” she said.

She now hopes to continue sharing her story.

“If it helps a few people, then I’ve done my bit.”

Betty opens up to James about the mental impact of her health condition, MRKH.

At the start of the show, Betty and her younger sibling admitted they had not been very close in the past.

But their relationship has developed throughout the series and in Wednesday’s episode, James became so emotional after their discussion about Betty’s condition that he asked for a hug from the production team.

For women who want to have children despite their diagnosis, options such as IVF surrogacy and adoption are available.

Women with MRKH still have functioning ovaries which produce healthy eggs and female hormones.

Last year, surgeons carried out the first womb transplant in the UK, whose recipient was a 34-year-old with MRKH, the donor being her older sister.

The director of peer-led charity MRKH Connect, Charlie Bishop, said Betty’s disclosure on the programme was “incredible”.

“The courage to share in that forum so openly and have that vulnerability on a show that’s not designed for that kind of thing is incredible,” she told the BBC.

Charlie, who is now 40, also found out she had MRKH at a young age – when she was 17.

“None of us are prepared for this because none of us are ever taught that this will be the case,” she said.

“We are told periods will happen and when they don’t happen, we’re not told what that really means. I was told ‘you’re just a late starter, it will happen’.”

She believes the biggest challenge for her was the impact her diagnosis had on her mental health.

“It took a very long time to process that and several years to understand what it meant for me”, Charlie explains.

“I had feelings of grief and trauma and didn’t understand how to manage these feelings.

“It’s hard to put into words how I felt at that time.”

Daisy Jonas, 26, said she was “naive” about the impact MRKH would have on her life when she was diagnosed at 15.

Daisy now has a two-year-old son who was born out of surrogacy after her mother offered to carry a baby for her and her husband.

“I always knew I wanted to be a mum,” she told the BBC.

“My mum offered to have a baby for us and we said, yes please.”

Daisy said she still struggles with coming to terms with her condition, and not being able to carry her own child.

“I’m also a midwife so I can’t really escape pregnancy,” she said.

“But even though I won’t give birth myself, I can still be a part of that process for the people that I care for at work.”

She added that she was emotional after watching the video of Betty talking about her diagnosis.

“I’ve never heard anyone talk about MRKH in so much depth publicly,” she said.

“It just takes one person to start the conversation.”

For many with MRKH, Charlie says, disclosure is the hardest part.

She argues people tend to feel embarrassment and shame about the condition initially, and often don’t know how to share their diagnosis with family and friends.

Conversations around infertility, children and sex can be especially difficult.

“We need to normalise these discussions and make it easier for people to see and interact in a way that is comfortable for them,” she continues.

She hopes the scene on Wednesday’s programme is an opportunity to continue raising awareness of the condition and “build on what Betty has started”.